The Plot Thickens: Reading an Interwar Serial Novel

Johanna Wiggers reads a serial novel from 1931 one instalment at a time and traces the history of its reception.

Please note that all hyperlinks contained in this essay will lead to exclusively free further readings, mostly thanks to the Internet Archive, Trove and Overland archive.

Have you ever read a novel in serial form? In the age of on-demand entertainment and binge culture, this form of interrupted reading, complete with cliff hangers and delayed gratification, felt quite alien to me. I am not sure when I last read this way. However, sparked by the context of my research, I’ve been thinking a lot lately about serial fiction and how readers of the past engaged with it.

For my master’s project I am rereading and tracing the reception of four once popular German interwar novels written by women, all of which either debuted or were reprinted as magazine serials1. It has been bothering me that, with one exception2, there is no accessible record of them, let alone a complete one. This is because some issues either did not survive World War II or remain scattered across German archives. It does not help either that German digitisation is, on many accounts, still in its infancy and little is available online.

In Australia, it is a completely different story. It is home to Trove, a digital database hosted by the National Library of Australia, housing the world’s largest mass-digitised collection of historical newspapers (Bode 1). Since its 2009 launch, Trove has gradually unlocked a wealth of fiction previously buried in physical newspapers and magazines. In A World of Fiction, literary and textual studies scholar Katherine Bode highlights Trove’s potential in the context of literary studies, explaining how its vast newspaper and magazine data sets enable researchers to fill gaps in Australian literary history.

So, I decided to follow my interest in interwar women’s writing and track down a novel in Trove, hoping to find my own small gap in Australian literary history to fill. At the same time, I wanted to satisfy my curiosity of reading a historical serial novel how it was intended: in its original staggered publication.

I chose Veila Ercole’s 1931 novel No Escape as a case study, which I soon found was the first published novel written by an Italian Australian woman (more on why this novel specifically in a moment). Across 18 instalments from 21 January to 20 May 1931, No Escape tells the story of Leo Gherardi, an Italian doctor, who flees to Australia with his family in 1900, after his involvement in Socialist agitation at home in Bologna.

Reading this novel, I set myself rules to replicate an authentic serial reading experience and follow its instalments in The Bulletin, where it debuted as the winner of a novel competition in 1931. Since I did not have time to spread reading time over 18 weeks, I decided to read one instalment a day to mimic the wait time readers had to endure before getting their hands on the next issue a week later. I will share my reflections on the reading process after an analysis of the novel and its reception and share my speculations on Ercole’s motivation for writing this novel. However, first I will provide some historical context around serial fiction in Australia to set the scene.

Serial fiction has a long history across the globe, and for good reason. Media historian Graham Law explains that, beginning in the 18th century, when periodical production networks were already far more developed than those for works in book form, it was simply more cost-effective for publishers to print serials (3). This, in turn, made serials accessible to readers who could pay painlessly small instalments instead of paying for a full volume upfront (3).

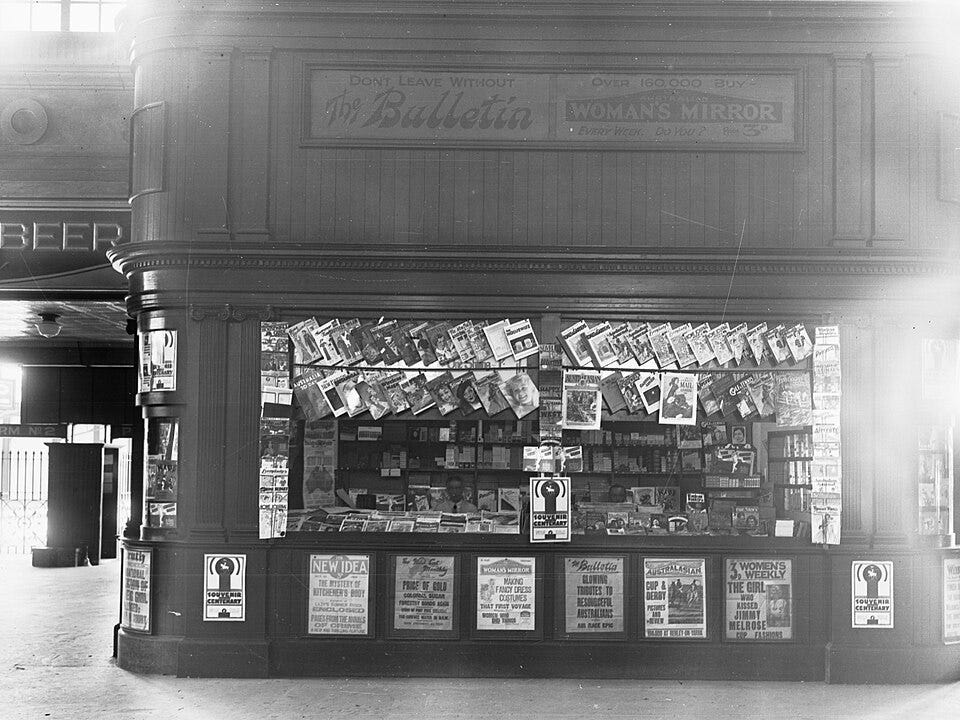

In the context of the burgeoning mass culture of the 1920s and 30s, Australia’s position as a colonial outpost contributed to the proliferation of serial fiction in the local market. While Australians were “drowning in a sea of new books and magazines,” as print culture scholar David Carter puts it, most fiction of the day was imported. Australian publishers rarely released more than three or four complete titles of local fiction yearly—so, curiously, even “‘Australian’ novels typically came from elsewhere,” usually London or New York (Carter 136). As a result, periodicals remained the primary publishers and distributors of Australian and imported fiction in the early 20th century (Bode 1).

The flood of fiction, as Carter describes, contained a wealth of women authored texts. Australian writer Drusilla Modjeska opens her influential 1981 study Exiles at Home: Australian Women Writers 1925- 1945 by making a point of just how influential women writers were, particularly during the 1930s, despite a largely masculine literary culture. Modjeska asserts that women, in fact, wrote the “best fiction of the period,” with writers like Miles Franklin, Eleanor Dark and Christina Stead in their prime (1). Access to publishing opportunities in magazines and newspapers certainly contributed to the boom of women authored fiction Modjeska outlines. Higher participation rates of women in literary spaces sparked conversation about the “feminisation of literature,” but opinions were divided on whether this was a good or bad thing (Modjeska 9).

Surprisingly, women were met with acclaim even in publications that long upheld a masculine outlook on Australian literary culture, such as the most well-known of its kind: The Bulletin. The Bulletin’s ‘best novel’ competition which ran from 1928 to 1932 put women writers in the spotlight. Women, in fact, dominated this prize competition. In its first year alone, three shared first place: Katherine Susannah Prichard with Coonardoo as well as Marjorie Barnard and Flora Eldershaw who co-authored A House Is Built. If you would have asked Vance Palmer, who was the only man to win this prize in 1929, he might have predicted this, since he claimed in a 1926 Bulletin article that “writing a novel seems as easy to almost any literate woman as making a dress” (3).

Palmer’s oddly begrudging admission of women’s talent for producing fiction would also have applied to the 1931 winner of The Bulletin’s competition: Velia Ercole. While I knew of most of the women writers mentioned so far, I had never heard of Ercole. Research into her life and work yielded little—and this, of course, intrigued me, making her novel No Escape the obvious choice for my serial reading experiment.

Velia Ercole has nothing but a short entry in the AustLit database, outlining the basic cornerstones of her life in just shy of 100 words: Ercole was born in the opal-mining town of White Cliffs in New South Wales in 1903 to an Australian-born mother of Breton and Irish heritage and an Italian father. She grew up in Grenfell, another small town in New South Wales, where her father found employment as the local doctor. In the 1920s, Ercole relocated to Sydney where she began working as a journalist for the Sunday Sun.

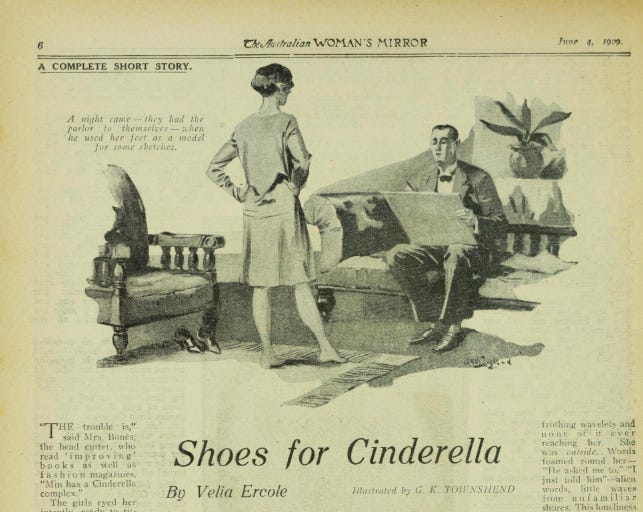

During this time, she began writing short stories. So, when she made her long-form debut with the novel No Escape in 1932, Ercole was already a known name in the cosmos of magazine fiction, with stories published in publications predominantly aimed at women, including The Triad, The Home, and The Australian Women’s Mirror. Across the 1920s and 30s, I counted over 30 short story publications written by Ercole (conveniently catalogued and linked on the Australian Women Writers website here and here).

While not all Ercole’s stories are tailored to the predominantly female readership of these upmarket publications, many of them are. They reflect the lives of women who looked to these magazines for relatable and aspirational models of modern femininity, with their colourful depictions of luxury and leisure. Ercole’s stories featured romances between typists and employers, unhappy wives dreaming of divorce and women otherwise looking to escape the drudgery of office work by going on lavish cruises or honeymooning in Kenya.

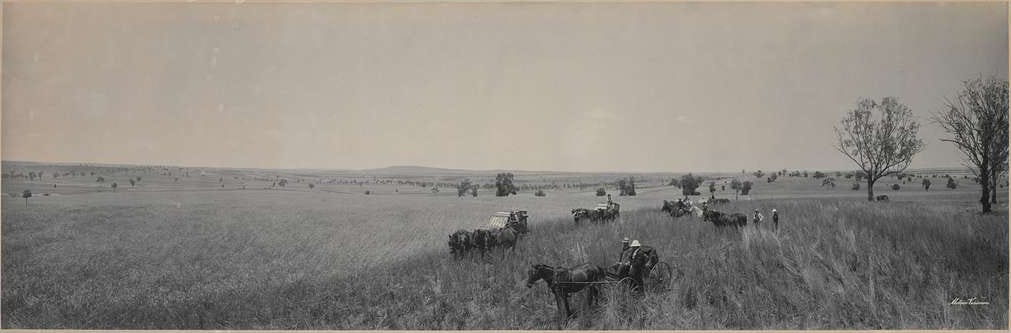

No Escape, in contrast, is a novel entirely different in tone and setting from the majority of Ercole’s short stories. The novel, on the surface, is not concerned with the viewpoint of the modern woman. Instead, it has all the hallmarks of what would have been deemed ‘serious’ Australian literature at the time: a lavishly described bush setting, offering a slice of life in a small New South Wales town and a male protagonist—much in line with output expected of the nationalist The Bulletin, which figured as a critical site of local literary culture.

What makes it interesting, however, is that No Escape centred on the experiences of an Italian country doctor, a nod to Ercole’s own upbringing, and discusses complex migrant experiences not only of protagonist Leo, but also of his wife Teresa. The Bulletin’s seal of approval positions No Escape as an overlooked yet significant document of its time, when read in the context of its role in furthering the Australian literary tradition. Although The Bulletin once declared ‘Australia for the White Man,’ it makes a concession to Leo’s Italianess and Ercole’s Italian heritage and gender.

I found No Escape’s instalments reliably located on the same two densely printed pages (28 and 29) across 18 issues from 21 January to 20 May 1931. Over this time, No Escape tells the story of Leo Gherardi, an Italian political exile, who flees to Australia in 1900 after his involvement in Socialist agitation during his medical studies in Bologna. Leo and his wife, Teresa, initially settle in Sydney, where two years later their son Dino is born. He hopes to make enough money as a doctor to buy a pardon and return to Italy, where a promising career in medical research seems to await. Teresa too pins all her hopes onto their return home since she has given up her career as a promising opera singer to marry and follow Leo to Australia. Five years into their temporary life in what Teresa describes as “at least the pretence of a city” Leo makes some bad investments in gold mining (Instalment 2, 28; Instalment 3, 28). As a result, the family is forced to move to Banton, a remote, fictional country town west of the Blue Mountains. Here Leo hopes to make fast money as the new head of the local hospital (Instalment 2, 29).

The first instalment opens in 1905 with a vignette from Leo’s life as a country doctor in Banton, delivering a baby into the founding family of the town, the Gilberts (Instalment 1, 28). The narrative then briefly pivots to establish the fictional lore of Banton, shaped by the rise and fall of the gold rush and the Gilberts’ assertion of power over the land in the 19th century. Ercole thus sets up the expectations of a family saga, hinting at the soon to be intertwined fates of the Gerardhis and Gilberts—Leo ultimately remarries into the family.

Across the first half of No Escape’s instalments, Leo, who first thinks of Banton as a “mill from which he would grind the money he needed,” develops a fragile sense of belonging in the town (Instalment 9, 28). Ercole skilfully weaves moments of doubt into Leo’s disparagement of what he experiences as a desolate and distinctly Gothic place, charred by bushfires and scarred by abandoned gold mines. First, his derisive laughter at the absurd idea of staying is merely tinged by “a hint of irresolution” (Instalment 4, 29). But soon, developing a curious contentment with his rural routine, he decides to win the confidence of the townspeople, who have been apprehensive about his foreignness. Leo is eventually successful in doing so, and Banton’s inhabitants respond with a generous donation towards his medical practice (Instalment 9, 28). Suddenly, his family’s planned departure begins to feel like a betrayal to the people in Leo’s eyes.

“The town and the people she hated encroached on every moment of her life”

Leo’s wife Teresa, who senses the shifting allegiance of her husband, feels betrayed in turn. This marks the breakdown of the couple’s relationship. To her, Banton remains an alienating place, likened to a prison. For example, when Leo urges Teresa to mix with the local society women at a tennis match, she enters the fenced-off court “like some dark, ruffled little bird seeking admittance to this cage of gay, brightly plumed creatures” (Instalment 4, 29). During a picnic at the match, Teresa is met with a complete lack of understanding by Banton’s society women, especially when Teresa dismisses their romantic ideas of Italy, eliciting “slight disgust” and the suspicion that she must be of “peasant origin” (Instalment 4, 29). In encounters like this, Ercole highlights not only Teresa’s sense of entrapment but also comments on the broader confinement experienced by Banton’s women—so small-minded and insular that they respond to Teresa’s culturally different viewpoints with outrage. Teresa ultimately refuses to further engage with Banton society, actively resisting Leo’s mandate.

As Teresa grows increasingly despondent, Leo begins to regret marrying such a “morbid” woman. When he reveals this in a fight, “something snapped in Teresa’s brain” (Instalment 9, 29; Instalment 10, 29). Chained to Banton by her love for Leo, who no longer seems to return her feelings, Teresa dies by suicide. Ercole depicts Teresa’s death with compassion, framing her breaking point instead as a form of emancipation. After her death, Leo’s desire to return to Italy rekindles but he decides to forgo any personal happiness by staying in Banton, believing that he deserves “a lifetime of self-punishment” for betraying his wife (Instalment 11, 28).

In what feels like a second act, the story skips ahead a year to find Leo unexpectedly in love with a local widow and a member of the Gilbert family, Olwen. Resisting his attraction at first, he later acquiesces and decides to remarry. In contrast to Teresa, Olwen, belonging to the town’s founding family, becomes the “type of doctor’s wife Banton understood and demanded” and aids in further integrating Leo into the local community (Instalment 16, 28). Olwen is the epitome of the colonial mindset, at home in the landscape, with a sense of belonging curiously legitimised by her settler ancestors who founded the town for whom she feels a “strange, half-religious veneration” (Instalment 15, 29). In contrast to Leo and Teresa, Olwen’s eyes “have been trained to a perception of nature; to find beauty in a peeling white gum” (Instalment 13, 28). In 1913 Olwen delivers a son, who she hopes will farm the land like her forefathers. Leo’s passion for his new wife begins to dim, since their cultural difference seems to be unbridgeable and he feels once again trapped, when suddenly the onset of WWI offers an opportunity to leave. Naively, Leo, feeling a secret “violent joy”, thinks only of adventure and release. “This meant Escape!” he thinks to himself (the novel’s title begs to differ).

The horrors witnessed at Gallipoli soon make Leo long for Banton, now ironically a “place of sweet and tender enchantment” (Instalment 17, 29). Upon being transferred to Cairo he finds little kinship with the Italians he encounters but feels at ease around Englishmen. Despite harbouring the fantasy of going back to Italy on his own he returns to Australia, where in resignation, he continues his rural life. The town begins to grow as returned soldiers receive land around Banton. Olwen convinces Leo to buy land himself, pushing him into the role of dutifully active citizen. In a reversal of fates, it is Olwen who ultimately holds power over Leo, binding him to Banton against his will—there is No Escape.

“He would stay here and rot…. In her arms”

By the end of reading, I was convinced Ercole intended to write a decidedly Gothic Australian family saga, despite presenting on the surface, a story of ‘successful integration’ of an Australian migrant into an Australian community. The novel is pervaded with a disconcerting sense of entrapment, particularly with regard to Leo’s first wife, Teresa, which allows Ercole to highlight the gender inequalities persisting in colonial society and within the institution of marriage.

With moments of sharp satire and well-developed characters, I enjoyed picking up this novel every day for eighteen days. The two densely printed pages of each instalment are just enough to sustain interest, making you impatiently wait for the next one. There were only a few instances when the story felt fragmented in a way that served the logic of periodical printing rather than the pacing of the story. I also did not encounter any hair-raising cliffhangers, that would have pointed to the novel’s production with this format in mind.

After a while, I came to appreciate the overall change of pace reading in serial instalments enforces. Just as in real life, there is no instant resolution to the problems of the characters you have been following for weeks.

I could easily imagine how a female reader of the day might have briefly escaped into this Gothic rural world, or perhaps related to Teresa’s sense of entrapment within her marriage. That the story did anticipate female readers is suggested by accompanying advertisements for The Australian Women’s Mirror, The Bulletin’s women’s magazine.

I was also interested in gauging reader responses of the day. What is fantastic about magazines and newspapers is that they hold many clues as to the reception of literature—in this case they were mostly positive. Shortly after its release, the Sydney Morning Herald, for example, called No Escape a “competent piece of work” despite some “unproductive passages” and Ercole’s apparent addiction to “disagreeable details” including Teresa’s death and Leo’s medical profession—the very Gothic elements that stood out to me (April 8, 1932).

Beyond the newspaper accounts of the early 1930s, there is little critical attention paid to Ercole’s oeuvre. A prominent, early exception is a dedicated author’s profile in Colin Roderick’s collection of 20 Australian Novelists (1947). Roderick highlights Ercole’s No Escape as a “well-structured novel” with a “close-knit plot” that develops a realist portrayal of “a common conflict to thousands of foreign immigrants in Australia”—the struggle to assimilate (112). Roderick, in fact, deems it “so realistic” and “truthful” that “it might as well be biographical” (112).

The next piece of criticism I found during my research would mark a three-decade gap before the next critic expressed an appreciation of Ercole’s work. In 1978, Winston Burchett argued for a series of paperback reprints of “Forgotten Novelists of the Thirties” in Overland (that is, if one could only find “some philanthropic publisher”) (38). He makes a case for No Escape’s inclusion in such a dreamed of series: Not only is the novel “incredibly readable” but also “as relevant today as when it was written” due to its discussion of migrant experiences (Overland 72 1978, 38). Burchett’s hopes would remain disappointed; the novel was never reprinted. However, the accessibility of the novel on Trove might have consoled him.

Ercole receives another mention in a 1998 issue of Overland, in which Roslyn Pesman Cooper examines No Escape through the lens of Italian women in immigrant fiction. Cooper points to the near invisibility of Italian migrant women during the interwar period (the mass immigration of Italian women would only begin in the 50s and 60s). Similar to my reading of Teresa, she commends Ercole for not framing her as a “helpless victim” (68).

In all these critical revisits of Ercole by Roderick (1947), Burchett (1978) and Cooper (1998), it is No Escape alone that attracted praise and engagement. I can only conclude that since it is Ercole’s only novel set in Australia, and all three accounts highlight its engagement with migrant culture and colonialism, readers and critics seem to view it as the only one that qualifies as a ‘truly’ Australian novel.

Such ‘Australian stories’ were clearly unpopular with publishers outside of Australia at the time. In a short profile in February 1932, which appeared in The Herald, Ercole expressed that there was simply no demand for “Australian settings” in the publishing industry which largely operated overseas (The Herald, Feb. 1932). Therefore, the initial serialisation in The Bulletin might have been Ercole’s only means of getting this novel published at all. Without the well-established periodical market of the day, and the incentive of a £500 prize, No Escape might have never found any readers.

No other novel of Ercole’s featured Australian or Italian characters again, and after the release of her follow up novel Dark Windows (1934) she abandoned writing under her own name entirely. After moving to Britain, Ercole wrote commercially successful romance novels using the nom de plume Margaret Gregory (her second name and husband’s last name). This rebranding appears to have occurred purely on financial grounds. Ercole noted in The Herald that the demands of the literary market meant that “she had to alter her style altogether” and adapt herself to write “happy stories with cheerful endings” (The Herald, Feb. 1932). Her writing post- No Escape, produced outside of Australia, would therefore bear no trace of her proclivity for “disagreeable details” the The Sydney Morning Herald criticised in No Escape. Ercole’s move overseas and rebranding as an English romance writer subsequently contributed to the erasure of her status as an acclaimed Australian author and her place in Australian literary history.

Through this historical serial-reading self-experiment, I discovered a complex, forgotten text that few critics have discussed beyond its realistic portrayal of migrant experiences in Australia. My reading of No Escape has highlighted the novel’s critical engagement with the marginalisation of women in colonial society—which, in turn, also affected Velia Ercole’s own writing career.

Ercole’s fate is shared by many Australian women writers, whose works have fallen into obscurity, have never been reprinted, or have only ever been published in serial form. However, today, novels like No Escape are potentially just a few clicks away. As Katherine Bode reminds us, Trove consolidates over 9,000 serialised works of fiction in its newspaper collection (7). Amongst them are Australian novels which have entirely disappeared from cultural memory.

Click here to view the works cited in this piece.

Johanna Wiggers (she/her) is a MPhil student at James Cook University, currently researching representations of modern femininity in the literary context of the Weimar Republic. Her research interests include modernism, middlebrow, and women’s writing, and interwar print culture. She is the co-editor of Exhume alongside Bianca Martin.

If you’re curious, I am talking here of two novels by Vicki Baum (Helene (1928) and Grand Hotel (1929) which debuted as serials in the Berliner Illustrirte Zeitung, and Irmgard Keun’s Gilgi One-Of Us, reprinted in the German Social Democrats official newspaper, and The Artificial Silk Girl, reprinted in French translation in Marianne after the Nazis seized power and banned her novels.

The exception is Irmgard Keun’s 1931 novel Gilgi- One of Us, which is, due to it being printed in old German Fraktur typeface, very hard to read for me.

‘’Writing a novel seems as easy to almost any literate woman as making a dress” - Oh Vance, have you ever tried to make a dress?! This jewel of a quote made me laugh out loud! Johanna you make this deeply considered, well researched, beautifully argued essay look so deceptively easy as well. A joy! Congratulations!

Superbly argued, extensively researched, a gloriously idiosyncratic (in 21st century terms) reading practice and a wholly persuasive (and engaging) series of well-contextualised interpretations. Thanks.